(with permission from Poetry Ireland Newsletter)

Hard to believe I’ve handed in my fifteenth issue of Poetry Ireland Review. How did that happen? The initial idea was to do eight issues as the organisation felt that the Review, at this stage of its journey, would benefit from a longer span of editorship. Eight turned to twelve and then I was asked to hold the fort for another three issues as PI went through some changes of its own, and, all pleas for mercy having fallen on deaf ears, this I agreed to do.

Now that it’s over, what will I miss? Editing a magazine is a strange business, hard to quantify, or even to describe exactly. The activity itself lies somewhere between sloth and panic, and between intent and happenstance. Vague ideas slide around the back of the mind, poets who might be encouraged to submit, themes that might be tackled, writers that might be prevailed upon to deliver a think-piece. What about Wales? Afghanistan? What about Mangan, MacNeice, Mandelstam? Some things are there to be dealt with: the massive pile of submissions, for one. For many editors this is the most daunting aspect of the job. A magazine like PIR, with its national and international remit, attracts a dizzying volume of submissions. Many of these are what I’d call routine despatches – little bundles fired off to every journal that appears on a list, where the poet rarely bothers to read the journal and get a sense of what might be acceptable. Most of the submissions are not publishable – they’re just not interesting enough, not well enough written. Reading them can be a dispiriting chore. And yet there are the real finds, bright poems by unfamiliar writers, good work by established ones, and the small pile of definites begins to grow. You cheer up.

You quickly realise that very many good poets, particularly Irish poets, don’t submit work. You also realise that a lot of poems are well enough written to be publishable – and yet they don’t excite. They do not cause the hair on the back on the neck to stand up. The editorial heart doesn’t stop, nor breath shorten. Their language is inert, the subjects are boring. Poets can often seem to be working a narrow little seam of private experience. They don’t seem to get out much. This seems to be particularly the case with poetry in English. An enormous variety of poetry of every possible hue is written in English but only a pbrokenarticular strain of it ends up, for the most part, on the PI desk. The editor in search of poetic adventure has to labour a little to find it.

PIR is an Irish magazine, but I didn’t take that to mean a magazine of Irish poetry. It’s true that there is a serious effort to assess Irish-published work and to feature work by Irish poets, and these are both built into the fabric of the Review. But – and here comes some good old bias – a large part of me thinks that the whole notion of Irish poetry is fairly boring, a kind of branding exercise for a product few, if put to it, could really define. The currents of poetic influence flow across continents and languages and few poets would seek to confine themselves within national boundaries. The dismaying parochiality of so much of Irish critical and cultural discourse – not least the flawed concept of ‘Irish Studies’ – shouldn’t blind us to the internationalism that is the lifeblood of poetry. Those who assume the exceptionality of Irish poetry will witter on about the lines of influence from Yeats to Heaney to Muldoon and ignore the fact that Montale, Pessoa, Celan, Bonnefoy and a host of other unacknowledged legislators have long since gatecrashed the party. I put a lot of poems in translation into the Review not least because a good part of my everyday reading consists of exactly that, and a magazine may as well be as attentive to the idle browsing of its editor as to his, em, considered interventions. But I actually don’t know any serious practitioners who don’t have an ear cocked to the news from elsewhere, and aren’t excited by what discover from one end of the planet to the other. We are at home in our language and necessarily imprisoned in our own little context, but the spices we cook with are as likely to be imported as home-grown.

Have you no funny stories to entertain us? Editing is an exciting and dangerous business, isn’t it? Did you never get a clatter on the ears or a box on the jaw for your pains? If you haven’t made enough enemies in life, then you need a spell in an editor’s chair to set the balance right. The stock in trade of editing is disappointment. Back in the eighties we paid doleful visits to what we called the Careers and Disappointments Officer to contemplate the bleakness of our futures, and being an editor is a bit like that in that most of those who knock on the door are not going to walk out smiling. I often had to say no to good work because there simply wasn’t room for it, and found very little pleasure in the god-like decision-making aspect of the job. You’re aware of how idiosyncratic personal taste is – and yet your job is to trust your own instincts and not let too much else get in the way. You need to believe that the final result is important: a magazine that can stand on its feet and not be hobbled by platitude, cosiness or corporatism. And then you need to go away and have a drink and forget about it.

I was lucky to have in the background an organisation and individuals fanatic in their devotion to the persistence of this journal, and an assistant editor, Paul Lenehan, whose eye for detail far exceeded mine, and I was equally blessed to have a range of contributors prepared to risk sending poems and to sit up late perfecting reviews and essays. The survival for more than a year of any literary outlet is miraculous, and maybe it’s only professional organisations that can sustain the effort indefinitely. For me it’s great to be able to go and to know PIR will continue to drop through the letterbox every three months. The editor is dead. Long live the editor.

Tuesday, November 06, 2007

Wednesday, October 10, 2007

The Old Man Speaks with his Soul

Went to see the launch last night in the Goethe-Institut of Der Alte Mann by Günter Kunert translated into English by Hans-Christian Oeser and into Irish by Gabriel Rosenstock. The book is part of a series of trilingual poetry collections published by the Irish language house Coiscéim. Kunert is one of Germany’s leading post-war poets. He was born in Berlin in 1929 and as a ‘Mischling’ (of mixed decent – his mother was Jewish) was deemed unfit to finish his secondary schooling or serve in the German army during the war. After the war he lived in the GDR, but after signing a petition in 1976 against the state’s stripping of Wolf Biermann’s citizenship he subsequently lost his party membership, and was allowed to leave the GDR in 1979. As well as poetry he has written short stories, novels, television plays and screenplays. Poetry translations in English include three poems in Michael Hamburger’s German Poetry 1910-1975 (Carcanet, 1976), several poems in Charlotte Melin’s German Poetry in Transition 1945-1990 (University Press of New England, 1999) and three in Michael Hofmann’s The Faber Book of 20th Century Poems (2005). He is also one of four poets represented in Agnes Stein’s Four German Poets (Red Dust, 1979) – the others are Günter Eich, Hilde Domin and Erich Fried.

Brecht was a big influence on Kunert (two of his poems to Brecht are translated by Karen Leeder in her After Brecht: A Celebration, published by Carcanet last year), and this is evident in the pared down, laconic style of the work as well as its scepticism and irony. Here's a well known postwar poem in original and translation which gives a sense of his style:

Über einige Davongekommene

Als der Mensch

Unter der Trümmern

Seines

Bombardierten Hauses

Hervorgezogen wurde,

Schüttelte er sich

Und sagte:

Nie wieder.

Jedenfalls nicht gleich.

About some who survived

As the man

Was dragged from the ruins

Of his bombed out house,

He dusted himself down

And said

Never again.

At least not right away.

And another well known poem, ‘Film Put in Backwards’, in Christopher Middleton’s translation

When I woke

I woke in the breathless black

Of the box.

I heard: the earth

Was opening over me. Clods

Fluttered back

To the shovel. The

Dear box, with me the dear

Departed, gently rose.

The lid flew up and I

Stood, feeling:

Three bullets travel

Out of my chest

Into the rifles of soldiers, who

Marched off, gasping

Out of the air a song

With cam firm steps

Backwards.

Der Alte Mann spricht mit seiner Seele is a sustained reflection on old age, full of grim humour:

THE OLD MAN

considers his toes. How fast

my nails are growing. Regular

claws. Is that abnormal or

is it biological fact? If only

the same happened to the hair

on your head, you’d have

a mane. Like Beethoven.

But then you’d be deaf!

Ergo: let’s go for the nails.

The translators’ notes at the back are a very useful (and all too rare) feature and show the extent to which the translation challenge is heightened by the allusiveness of the poems; they constantly and often playfully engage with German tradition in a way that can make them difficult to translate. Here are a few lines to illustrate the challenge:

Nikolaus Copernicus, der

polnische Schlawiner, stahl

mit die Zuversicht

ins göttliche Universum. Da steh’

ich nun, ich Armer Tor,

und bin bloß ärmer als zuvor.

Nicholas Copernicus,

that Polish rogue, robbed

me of my trust in a

universe divine. And here

I stand, with all my lore,

poor fool, just poorer than before.

The note to this points out that the final lines in the German directly quote the opening of Goethe’s Faust: ‘Da steh ich nun, ich armer Tor,/und bin so klug als wie zuvor !’ – ‘And here I stand, with all my lore,/Poor fool, no wiser than before.’

Here's one of the poems in the original followed by two translations, to give a flavour of this trilingual book.

DER ÄLTE MANN

blättert in seinen Telefonverzeichnis.

Alles Nummern von Toten. Wie

erreiche ich euch, Freunde.

Die Drähte sind gekappt, die

Sargdeckel versiegelt. Meine Stimme

dringt nicht mehr durch

in den ewigen Frieden. Mit

Antworten rechne ich nicht mehr.

Eure Fotos schweigen herzlich.

Als Schatten treffen wir uns

wieder einmal, ohne daß die

einander etwas zu sagen hätten:

Als daß wir uns

im Hades so verlassen fühlen

wie zu Lebzeiten.

THE OLD MAN

leafs through his address book.

All those numbers of the dead. How

can I reach you, friends?

The wires are cut, the

coffin lids sealed. My voice

no longer penetrates

the everlasting peace. No

more do I anticipate replies.

Your photograph keeps a cheery silence.

One day we shall meet again

as shadows with nothing

to say to each other:

Except that in Hades

we feel as abandoned

as we felt when alive.

AN SEANÓIR

is é ag gabháil trína leabhar seoltaí.

Uimhreacha uile na marbh. Conas

teacht oraibh, a chairde?

Gearradh na sreanganna, séalaíodh

na cónraí. Ní thollann

mo ghuthsa a thuilleadh

an tsíocháin shíoraí. Nílim

ag súil le freagraí níos mó.

Is binn bhur ngrianghraif ina dtost.

Casfar ar a chéile arís sinn

lá breá éigin inár scáthanna dúinn

is gan faic le rá againn

ach amháin in Háidéas

go mbraithimid chomh tréigthe

is a bhraitheamar nuair a bhíomar beo.

Günter Kunert, Der Alte Mann/The Old Man/An Seanóir. Translated into English by Hans-Christian Oeser. Gabriel Rosenstock a d’aistrigh go Gaeilge. Coiscéim.

Departing from Ourselves

(with thanks to The Irish Times, where this first appeared)

W.S. Merwin, Selected Poems. Bloodaxe Books.190pp. UK£9.95

The first poems that W.S. Merwin wrote were hymns for his Presbyterian minister father and in a way the impulse stuck; the poems he has written over a long career are impelled by belief. He is a poet of strong passions, as an environmentalist and pacifist who writes quietly and subtly and often to great effect. He started off with the expected accomplishments of a poet of his generation (he was born in New York in 1927): the smoothly articulated poem, a kind of off-the-peg, generic rhetoric. But then, as did his whole generation, he began to simplify, to look for the essentials that would leave enough to drive a poem but keep it as bare as possible, close to experience but unadorned with grandiosity.

Not that simplicity of form means simplicity of content. Merwin aims always for clarity but his thought is subtle. There are the very effective directly engaged poems like ‘For a Coming Extinction’: ‘Grey whale/Now that we are sending you to The End/That great god/Tell him/That we who follow you invented forgiveness/And forgive nothing...//Tell him/That it is we who are important.’ Or the bitter anger of his anti-Vietnam poem ‘The Asians Dying’: ‘When the forests have been destroyed their darkness remains//...Rain falls into the open eyes of the dead/Again again with its pointless sound/When the moon finds them they are the color of everything.’

But there are also the poems which struggle with the limits of the sayable. In an interview in The Irish Times he said that ‘poetry is about what we can’t talk about. It’s about what we can’t express.’ A great deal of Merwin’s work hinges on this sense of what language is not capable of expressing, like the pencil that hides all the ‘words that have never been written/never been spoken/never been taught’, or like the bleak acknowledgement of ‘Elegy’ (not, alas, in this book) which reads in its entirety ‘Who would I show it to’.

He writes about nature without sentimentality, without trying to hold on it and make it signify. He returns frequently to the human remove from the world – there’s often a sense that we’re hardly in the world, hardly know it, but stumble half-blindly towards it, as in ‘Hearing the Names of the Valleys’:

the color of water flows all day and all night

the old man tells me the name of it

and as he says it I forget it

Often too, man is a devouring insect ‘eating the forests/eating the earth and the water//and dying of them/departing from ourselves//leaving you the morning/in its antiquity.’

He has published a large body of work, and is also a distinguished translator of poetry, yet the reputation has been largely an American one. Even if few might see him, as the blurb claims, as ‘the most influential poet of the last half-century’, this fairly slim selection usefully introduces several decades of the work of a significant poet who, when asked what he most looked for in a poem, responded immediately: ‘Surprise’.

Thursday, June 21, 2007

The End of the Poem

Paul Muldoon, The End of the Poem, Oxford Lectures on Poetry. (Faber and Faber, 2007), UK £25.

How do you write about poetry? And when you write about poetry, who are you writing for? Paul Muldoon’s book gathers the fifteen hour long lectures he delivered during his Oxford professorship, so the initial audience would presumably have been largely an academic one. The tone and pitch of these talks reflect that; there’s an elaborate cleverness and often an archness of address as Muldoon plays with the forms of academic discourse. But it’s very much also a book for readers of Muldoon’s poetry: its methods, ifs shifts and feints, its teasing humour, its incessant connection-making, are precisely those of the poems. The poetry lover will segue easily from Horse Latitudes to The End of the Poem and the voice and the territory will be comfortingly familiar. Muldoon’s first decision was to to focus each of these lectures on a single poem, which makes for a pleasing structure, and promises the kind of forensic analysis of particular words in particular places you might expect, and relish, from a practising poet, as well as a practical way of tackling some the ‘ends’ of poetry. It immediately foregrounds the primacy of the poem rather than the poet: these are not to going to be encapsulations of a total oeuvre so much as reflections of a personal choice of a single significant text.

The choices themselves are both expected and surprising. On the one hand a canonical list: Yeats, Hughes, Dickinson, Bishop, Frost, Lowell, Moore, Auden – your average course in a certain kind of twentieth century poetry – and on the other, poems in translation by Pessoa, Montale, Tsvetayeva. The method of close textual analysis of a single poem work less well here, since the attention is, necessarily, on translations rather than originals and Muldoon’s highly culture-specific ruminations don’t easily migrate from English. Translation of its nature imports its targets into the terms of the source culture, but that doesn’t mean we can really see a Montale or a Tsvetayeva in a tradition of English-language perception. But more of that later.

What the focus on single poems does is to shine the torch on very specific parts of the process: a microscopic close reading where the attention is on the individual word. But actually the interest is often more on how the particular lexical choice ramifies outward, relates to other words in other poems. Muldoon’s variety of close attention is about making connections. He is very interested in how poems relate to each other, but it’s a very personal and idiosyncratic sense of connection that drives the essays. His choice of method allows him a leisurely, meandering, serendipitous reflection where one thought leads to another which prompts another in closed circles of associative thinking. The essays don’t so much discuss the poems as circle purposefully around them, from the critical to the biographical to the loosely speculative and ruminative, led by ear or memory or some other prompt to an unexpected destination. The result can be disconcerting in that the poem under discussion often seems to crumble under the weight of rumination and you are left marvelling at the connections rather than any more enlightened about the poem itself.

This is probably to miss the point. This is a book at least as much a tour around the brain and imagination (the brainy imagination?) of Paul Muldoon as it is an engagement with poems. The primary relationship which the reader has in these pages is with the darts and shifts and lateral thinking swagger of the guide. All poetry criticism by poets does this to some extent, but here you have a real sense that the poet is as much discovered as discoverer. You don’t come to these essays to be released into the otherness of other poets so much as be coiled back into the mind that considers them. The book opens with a discussion of Yeats’ ‘All Souls Night’ which moves easily from discussion of sound patterning, ‘the mimesis of the tolling bell in the predominantly spondaic metre of what is now the first line’ to a history of the festival of All Souls Night and its relation to Halloween and Samhain, which was ‘if you recall, the name of the house magazine of the Irish Literary Theatre...’ to an anecdote about a college professor introducing Yeats as the author of ‘Ode to Psyche, ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ and ‘Ode on Melancholy’, which itself introduces the core idea: the relationship between Yeats’ poem ‘All Souls’ Night’ and Keats, underscored in his mind by the fact that one hundred years elapsed between ‘To Autumn’ and the writing of ‘All Souls’ Night’ and that Yeats’s poem was one hundred lines long.

Some of this argument is plausible and interesting, although the certainty of the statements is surprising. Not x may be connected to y, but x proceeds unmistakably from y. This may be part of the game Muldoon plays consistently throughout the book – of turning academic seeming procedures on their head. On the line ‘The coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine’, Muldoon, for instance, has ‘no doubt – though some will say I should – that the musk ghosts the muscatel...’

The book is peppered with these sort of certainties or mock-certainties. Another oddly persistent thread is the focus on the secret life of poems where words or ghosts of words or unchosen synonyms of words are codes concealing, as often as not the names of the poets. The occurrence of the word ‘drains’ in Keats’ ‘Ode to A Nightingale’ somehow connects with ‘lees’ and is therefore ‘an indicator of what lies under the surface these lines [by Yeats] which centre on his wife, Georgie Hyde-Lees.’ That Nomen est omen becomes one of the subplots of the argument. In Frost’s ‘The Mountain’, for example, we are to take it that ‘The mountain held the town in a shadow’ contains a reference to the name Robert Lee Frost, since you could also render it ‘The town was in the lee of the mountain’, while in ‘Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening’, ‘woods’ recalls ‘forest’ which is a near anagram of Frost. And not just Frost: Marianne Moore is at it too who, in the word ‘fen’ in

If you will tell my why the fen

appears impossible, I then

will tell you why I think that I

can get across it if I try

is really referring ‘to the reading of her own name as “marsh”, the second sense in which it appears in the OED...’

There’s an illuminating Muldoon moment in the Moore essay: Moore he says, may be worrying that she’s too Moorish ( in the Moors of Spain sense) and then he remembers reading in the third edition of the Encyclopaedia Brittanica that ‘ the greatest peculiarity in Moorish architecture is the horse-shoe arch’ and then he comments on his own methodology:

Now, I know that this kind of reading may sometimes seem a little fritillarian (in the dicey sense which underlies both the butterfly and the flower so familiar to this audience), perhaps a little fiddle-headed, but what can I do? I’m sitting at a desk I acquired from the gentleman who looks after surplus furniture at Princeton. His name is Sam Formica. On the desk are two books. One is The Botany of Desire : A Plant’s-Eye View of the World by Michael Pollan. The other is Archie G. Walls’s Geometry and Architecture in Islamic Jerusalem.

This sums up the dizzying parade of serendipity that characterises this book and make it a somewhat exhausting read. The sense of the connectedness of texts may be what drives the book but it takes a particular cast of mind to pursue and relish some of these connections which are imagined, intuited, guessed at since they mostly cannot be proven. In his lively discussion of Ted Hughes’ ‘The Literary Life’, which remembers a visit by Hughes and Plath to Marianne Moore in her Brooklyn eyrie, the occurrence of ‘stair’ and ‘nest’ in the opening lines

We climbed Marianne Moore’s narrow stair

To her bower-bird bric-à-brac nest, in Brooklyn

sends him both to Philip Larkin’s ‘The Less Deceived’ (‘...stumbling up the breathless stair/To burst into fulfillment’s desolate attic’) and the stare’s nest in Yeats’ ‘Meditations in Time of Civil War’.

Muldoon has extraordinarily highly developed auditory antennae which make him especially alert to the resonance of words, and this coupled with an absorption in the tradition of poetry makes it second nature for him to pursue a word back through its occurrence in other poems – almost as if poetry were an unending series of echoes and poets locked into a sonic cycle that makes every lexical choice seem somehow predetermined. In Muldoon’s sense of it, poems live in perpetual relation to other poems. There’s an interesting moment in the piece on Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘12 O’Clock News’ where he follows an Anglepoise lamp from Bishop to Derek Mahon’s ‘The Globe in North Carolina’, and on to Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children before returning to another version of the lamp in a Bishop short story. Again the trigger for this journey is verbal: it’s the occurrence of ‘poise’ in Mahon’s poem which leads him to Anglepoise. The rub of the word before the rub of the lamp, or the rub of the word as the rub of the lamp.

Mahon and Heaney both appear in this essay in terms of their indebtedness to Bishop. Since all poems echo other poems, it follows that all poets are indebted to other poets and much of Muldoon’s labours are directed at the forensic detection of influence. It’s as if the anxiety of influence had mutated into a near-pathological celebration of influence, or a sense that poems can only really function as the subjects of influence. But ultimately it’s reductive; you end up with a sense of poetry as a closed circle, an area of pure text, a hall of mirrors and echoes. Muldoon’s susceptibility to sound, to seeing patterns and structures of connectedness is in the end too definitively his own to be truly releasing for the reader.

The inter relatedness of all poems is most consciously taken up in the discussion of Montale’s ‘ Eel’, or more specifically, Robert Lowell’s translation of it, which is very much not the same thing. Before analysing and comparing a series of translations of this poem, Muldoon spends a good deal of time demonstrating the radical influence of Lowell’s version on Seamus Heaney. Lowell’s piling up of adjectives in a line like ‘where my carved name quivers,/happy, humble, defeated..’ is echoed in Heaney’s adjectival triadism in ‘lost, unhappy and at home’ and likewise the ‘black lace balcony’ in the second section of ‘The Eel’ – which, as Muldoon points out, is actually another poem Lowell mistook for a continuation of the poem – directly influences the ‘black plunge-line nightdress’ in ‘The Skunk’, the love poem ‘which, as we know, is already indebted to Lowell’s ‘Skunk Hour’. The problem is that this kind of criticism, for all the certainty with which it is presented, is just as likely to be a mile wide of the mark as it is to hit home. Seamus Heaney may indeed have been pushed around by these lines until he could take no more, but then again he may not have been. The black nightdress may simply have been a black nightdress, rather than a remembered Lowellism. Sometimes you can feel that Muldoon is over-addicted to the drunkenness of things being similar. He quotes these lines from an essay on translation by Octavio Paz

On the one hand, the world is presented to us as a collection of similarities; on the other, as a growing heap of texts, each slightly different from the one that came before it: translations of translations of translations.

It is certainly true that for Muldoon awareness of tradition is stitched into his sensibility, and both criticism and poetry are written within this awareness and often in conscious competition with his forebears; the work pursues a constant dialogue with Seamus Heaney, for instance, and you might wonder how persistent this thread would be if Heaney’s shadow were a little shorter in terms of geography and fame.

Another of the consistent interests in this book is his concern with how the ‘I’ of the poems relates to the actual biographical person, the degree to which the voice is the authentic bearer of news of the self, or is necessarily fictionalised, transformed by the act of writing. Self transformation, self disguise, the multiple dispositions of the self are engines of Muldoon’s poetry, and this is why a figure like Fernando Pessoa, and the heteronyms to whom he allocated his work, is important: ‘That Pessoa wrote in the guise or semblance of so many poets raises that much broader question about the extent to which the personality of any single poet may be thought of as being coterminous with his or her poems. . .’

Pessoa, in these kinds of discussions, can often seem more idea than poet: a handy exemplar of self-division, but he’s really too complex, too sui generis to be representative of anything, and the heteronyms are not so much clinically differentiated selves as aspects of the one unstable, xx Pessoa self. What he wrote under his own name or in the guise of a ‘semi-heternoym’ like Bernardo Soares are all fictions of instabilty, all manifestations of ‘the wound-up little train’ of the heart. In a letter in 1935 Pessoa explains that Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis and Bernardo Soares all proceed from different states of mind

How do I write in the name of these three? Caeiro, through sheer and unexpected inspiration, without knowing or even suspecting that I’m going to write in his name. Ricardo Reis, after an abstract meditation which suddenly takes concrete shape in an ode. Campos, when I feel a sudden impulse to write and don’t know what. (My semi-heteronym, who in many ways resembles Álvaro de Campos, always appears when I’m sleepy or drowsy, so that my qualities of inhibition and rational thought are suspended...

(To Adolfo Casais Monteiro – 13 January 1935, Zenith, 474)

In the same letter Pessoa also differentiates between a heteronym and a semi-heteronym. Bernardo Soares is a semi-heteronym ‘because his personality, though not my own, doesn’t differ from my own but is a mere mutilation of it.’

Pessoas’s heteronyms are an extreme version of what all poets do, and the greatest fiction of all is surely the notion that there is a single stable ‘I’ underlying anything written. ‘To fake is to know oneself’ (Fingir-se é conhecer-se), Pessoa wrote on another occasion, and that’s surely what is intended in the opening lines of ‘Autopsychography’, the poem which Muldoon discusses, given here in the translation by Edward Honig and Susan M. Brown

The poet is a faker. He

Fakes it so completely,

He even fakes he's suffering

The pain he's really feeling.

And those of us who read his writing

Fully feel while reading

Not that pain of his that's double,

But one completely fictional.

So on its tracks goes round and round,

To entertain the reason,

That wound-up little train

We call the heart of man.

Muldoon is actually less interested in Pessoa’s self-divisions than he is in applying his associative procedure to individual words, almost as if Portuguese and English inhabited the same linguistic continuum. Referring to the Portuguese text of the last quatrain of ‘Autopsychography’

E assim nas calhas de roda

Gira, a entreter a razão,

Esse comboio de corda

Que se chama coração.

Muldoon observes:

The use of the word gira at the pivotal point of the second line is a telling one, surely, since the first version of Yeats’s A Vision had been published in 1927, and would have been read enthusiastically by an occultist like Pessoa, particularly one with an interest in the “gyres” of history, in the automatic writing of Georgie Hyde-Lees, in Yeats’s theory of the mask.

How likely is it that the use of the perfectly commonplace Portuguese verb girar (to turn, rotate) was determined by a recherché word like ‘gyre’ in English? Muldoon seems to be applying the sonic values of English to Portuguese and extrapolating from that, but this is Pessoa viewed from outside, through the necessarily falsifying microscope of another language, in which, again, cara (face) seems conclusively related to Alberto Caeiro, ‘whose name also conjured up carneiro meaning both “sheep”. . . and “burial niche”. None of these lexical speculations tell us anything of real interest about the poetry. The forensic analysis of versions of Montale or Marina Tsvetayeva are too too much caught up in the webs of English language traditions to bring us close to the core of those poets.

In the end I came away from this book admiring its idiosyncratic brilliance but longing for the wider view; longing to escape from the associative labyrinth, from words, which may be an odd thing to say. Maybe what I’m really saying is that for me the close-up view can actually be distorting – and can only really work in conjunction with the wide angle shot of the work as a whole.

Friday, April 20, 2007

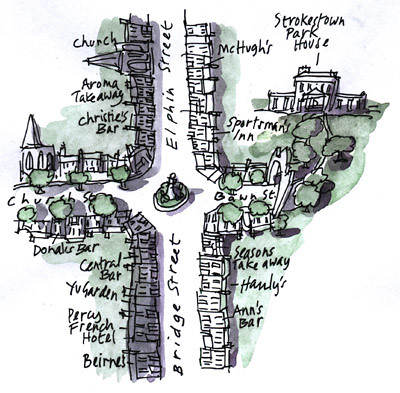

Strokestown Poetry Festival

Ireland’s friendliest poetry festival will again animate the small, attractive town of Strokestown, Co Roscommon this May Bank Holiday Weekend. I suppose I would say that, since I'm this year's Director. Packed into three intense days, the festival mixes well known with emerging poets, features readings in English, Irish and Scottish Gaelic from the poets shortlisted for the Strokestown Poetry Prizes, as well as including satiric verse and a pub poetry competition. This year’s guest readers include founder and editorial director of Carcanet Press, Michael Schmidt, who will read from his new book, The Resurrection of the Body, and another poet-publisher, Pat Boran, director of Dedalus Press and a well known poet and broadcaster. Audiences will also have a chance to hear Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Eva Bourke, Gerry Muphy, Moya Cannon ,Scottish Gaelic poet Meg Bateman and current Galway Writer in Residence Michael O’Loughlin. The acclaimed Gaelic Hit Factory with poet Louis de Paor and singer-songwriter John Spillane will also be appearing at this year’s festival, and local Strokestown man Tommy Murray will entertain audiences with a selection of favourite popular poems, in what has become a traditional event at the festival.

Among the highlights of the festival are the announcement of the Prizes: the Duais Cholmcille, sponsored by Colmcille, the organisation that promotes links between Gaelic Ireland and Scotland and the Strokestown International Poetry Prize. Both of these competitions offer prizes of €4,000, €2,000 and €1,000. The shortlisted poems, by poets from around the world, and all the festival details are available on the website.

The brown paper bags stuffed with backhanders of €500, €200 and €100 are waiting for the authors of the wittiest political or topical satires who will read their work at one of the most popular events of the weekend. This year’s judge is John Waters, who shortly after the festival will be travelling to Helsinki to see how his song fares in the Eurovision Song Contest.

Saturday, March 17, 2007

John Riley

John Riley’s early death — he was murdered by two muggers at the age of forty-one — combined with a history of publication by small presses and a talent that doesn’t lend itself to easy categorisation have tended to keep his work on the margins, admired by the few but generally unknown. This is a pity, because Riley was one of the finest poets of his generation. In his lifetime he published three collections, Ancient and Modern with Grosseteste Press, which he founded with Tim Longville in 1966, What Reason Was, and That is Today, published by Pig Press in 1978, the year of his death. The now out of print Collected Works (Grosseteste Press) came out in 1980. Carcanet published his Selected Poems, edited by Michael Grant, in 1995.

I had always been impressed by the few poems I came across in anthologies like A Various Art, edited by Andrew Crozier and Tim Longville. The impression I had of an extraordinarily gifted poet was borne out by the Selected Poems. I first came across this in The Secret Bookshop in Wicklow Street and owned it for about an hour before I left it somewhere. I was so taken with the poems I had scanned in the shop that I spent a forlorn couple of hours retracing my steps in an effort to find it. Some time later I wrote to Carcanet, who informed me that all copies of the poems had perished in the IRA bomb explosion. A little while after that a small parcel from Manchester arrived in my letterbox; a copy had turned up, slightly damaged, and they had sent it on free of charge.

What I like about Riley’s work is a wonderful musical clarity, a rhetoric which is at once backward-looking, tradition-nurtured, clearly English and at the same time distinctly modern, and the restless, searching intelligence that informs every line. That restlessness is evident in the formal experimentation that characterises the poems; each volume is riskier than the preceding, the poems more formally adventurous but always direct and always susceptible to the physical, the sensual, the immediate, the “great excitement among footnotes/away from the iron text”.

A good part of Riley’s manner stems from a talent that seems often divided against itself, that resists even as it embraces the lyric consolations. The love poems, and there are a lot of these, show this clearly. In fact his adoption of the love lyric as habitual means of expression also marks him out both from the ironies of the Movement style and its successors, and from the kind of distancing strategies of the Cambridge school with which he’s associated and in whose anthologies he appears. What I also like is the sense of double focus; in any poem there is the attention to the specific occasion but also where that intersects with the wider reality. He uses the lyric as a probe, as in this fragment from a poem whose title announces two large ambitions, at least one of which has been abandoned:

A stillness encompassing movement.

With enormous beauty still to answer to.

Blackness seeps through the closed door, douses the lamp.

It is a longing for the same world, and a different world.

(‘The World Itself, the Long Poem Foundered’)

The poem that first drew me to John Riley was ‘Second Fragment’, which I read in A Various Art. What attracted me, apart from the obvious formal grace, was the subtle way the poem survives its two opposing impulses, one lyric and celebratory, reaching for a kind of primal pastoral language, the other a sharp undercutting of that impulse, reaching for blunt instruments to disrupt the flow and a neutral, business-like phrasing.

Second Fragment

I put out the light and listen to the rain

Example taken from history— she loved

The rain: but that won’t do for she loves it still

And perhaps awake as I she lies at home

And listens to the rain that once beat on Rome

Or fell gently on the Galilean hills

This time of year is so beautiful

One can almost abandon oneself to it

It is the indifference of believers

That dismays, not the existence of others

We renew ourselves completely how often —

Daily we slit dumb throats and watch the blood run

I put out the light and listened to the rain

Hear how it falls: I wonder if love falls so

This poem ranges with a kind of calm restlessness from the specifics of its occasion across time, moods and subjects — love, faith, indifference, sacrifice, renewal, love again — yet there is a remarkable inevitability about the poem’s progress through its own disjunctions that is achieved by the delicate movement of the lines. A kind of impatience enters the poem in the second line and immediately interrupts the lyric poise of ‘I put out the light and listen to the rain’, a memory, abruptly recalled and brusquely set forth, of an absent lover. But the poem at this point resists the impulse to elegise or memorialise, though it makes effective capital out of the refusal. Something starts to happen in the poem after the double break between the second and third lines, the stop after ‘rain’ and the subsequent correction of the third line. The poem henceforth is a tug of war between its opposing modes, between

for she loves it still

And perhaps awake as I she lies at home

And listens to the rain that once beat on Rome

Or fell gently on the Galilean hills

and

This time of year is so beautiful

One can almost abandon oneself to it

It is the indifference of believers

That dismays, not the existence of others

or between ‘fall’, ‘fell gently’, ‘still’, the repeated ‘rain’ and the ‘dumb throats’ and the blood; or, again, between the ‘one’ that can almost abandon himself and the ‘I’ that begins and ends the poem. In fourteen lines the poets manages four personal pronouns: ‘I’, ‘she’, ‘we’, ‘one’ , five if we count the implied you (singular or plural) who is addressed in ‘Hear how it falls’.

The early poems are full of this play between the instinctive and the ratiocinative, the lyric and the counter-lyric, the ancient and the modern, to use the terms of the title of the first collection. In a sense, Riley is able to have the best of all possible worlds — the instrument he chooses can play all the old tunes, but can also produce a critical counterpoint. Argument and music shore each other up.

Ancient and Modern

Away from the house the snow falls slanting,

And trees almost in leaf in yesterday's sun

Put on today an elegant new shape,

A complex, streamlined growth. Did you ever see

The maidenhair (some few survive), a pre-

Historic tree? Limpid leaf, irregularity,

A touching intent to grow come what may

With perhaps insifficient means: a pleasure

To look on. As who shall see in winter leisure

Compassionate history take lucid measure

Of our too-obvious nourishment of hate,

And love that can't pass for understanding.

This is a poetry determined to play the traditional keyboard, to write from inside the tradition; in a sense it's anonymous, the lines could have been written by any number of poets.The following lines, from ‘This Time of Year’, strike me as more original, closer to the confidence of ‘Second Fragment’:

I stop to admire

The sky through an arch of branches

And thinking to go higher

Am caught in this gesture of pleasure

Appreciate the sagging hayrick

Its antiquated cottage form

Destined to keep cattle warm

Through winter

How much deeper must the days bite yet

There is a region where it doesn't matter

In the receding sky

Our gestures point to it

The poems have an immediate surface attractiveness that pulls the reader in. Sometimes, as in ‘Love Poem’, it’s an arresting sense of phrase and a sense of serious play. It's a poetry you want to say aloud:

Why shouldn't men blossom in the wilderness?

Hermits of course have their delights: they die

From weariness, renouncing every world.

This other death of ours need too much music —

Can you come out to play coming out

You've always been reluctant towards and I

Don't think too highly of myself for asking you. . .

If I had to pick a single poem with which to be consigned to the wilderness it would be ‘Poem’ (for Rilke in Switzerland) both for what it says and the sound it makes.

Poem

for Rilke in Switzerland

I have brought it to my heart to be a still point

Of praise for the powers which move towards me as I

To them, through the dimensions a tree opens up,

Or a window, or a mirror. Creatures fell

Silent, then returned my stare.

Or a window, or a mirror. The shock of re-

Turning to myself after a long journey,

With music, has made me cry, cry out — angels

And history through the heart's attention grow transparent.

Few poems could sustain a closing line like this, but I think Riley's rhetoric allows it.

Thursday, March 15, 2007

Thomas Kinsella’s Dublins

There are established personal places

that receive our lives’ heat

and adapt in their mass, like stone.

(Thomas Kinsella, from ‘Personal Places’)

It’s a critical commonplace that Irish writers are wedded to place, that their imaginations are awakened by the lure of specific territories: think of Joyce’s Dublin or Patrick MacCabe’s small town Ireland. Or think how Seamus Heaney’s recent District and Circle circles and remaps terrain familiar from forty years of previous work. Or again, how Roy Fisher’s poems grow out of Birmingham. ‘Birmingham’s what I think with,’ he once said, and it’s true of many poets that their places are part of their thinking apparatus, their essential imaginative equipment. It would be impossible to even think of Kavanagh without thinking of the places that were his subject. Sligo, Iniskeen, Barrytown, Raglan Road are planted squarely on the Irish literary map along with Eccles St and the Martello tower in Sandycove, yet not every writer uses place this overtly or identifiably – for some place is an underground stream pulsing deeply but mysteriously and only occasionally breaking the surface to course across the social, political and civic. For poets place is always as much a mindscape as it is a landscape.

Thomas Kinsella, whose own work is itself like an underground stream running out of sight of contemporary poetry, is like this. There are few bus tours to the area from Bow Lane to Basin Lane where he grew up and where so much of his work is set. Even if it is within sight of the Brewery, his Dublin will sell few beers, and doesn’t enter the Ireland that gets onto tea-towels or aeroplane headrests. And indeed, from the outset of his career he was seen as a poet who somehow transcended place, as if he were too magisterial for the mortar of the real. For me part of the thrill of the closing lines of ‘Baggot Street Deserta’, ‘My quarter-inch of cigarette/Goes flaring down to Baggot Street’ may have come from the fact that I could picture that trajectory, that I had been in Baggot Street and stubbed out cigarettes on the pavement, but for John Jordan in an early review there was ‘little or nothing in his verse (‘Baggot Street Deserta’ could as well be ‘King’s Road Deserta’ ) to suggest involvement with the city.’ This is both true and not true; it’s true in the sense that there is no overt memorialising of the city in the work, no comforting topographical identification, no sense of the city as city in the epic sense of Joyce’s Dublin, but it misses the poet’s intense and multi-faceted relationship with several Dublins: the city of his childhood with its narrow streets and dark yards; the Georgian city of his young adulthood, and the mangled boom-town with its ‘Invisible speculators, urinal architects,/and the Corporation flourishing their documents/in potent compliant dance...’

Had Kinsella been a different kind of poet and written more directly about his Dublins, he might have mapped them onto our consciousness. But by the time he turned his imagination on his city in earnest, his style had shifted from the crystalline clarities of his earlier work to a suggestive indirection, as he began to explore his own origins; many of the poems in the volume which marks a turning point in his career, New Poems 1973, are extraordinarily detailed recollections of his childhood, with a deliberate troubled intensity of focus that slows time down and creates a series of friezes as in ‘A Hand of Solo’, ‘Ancestor’, ‘Tear’ or ‘Hen Woman’

There was a tiny movement at my feet,

tiny and mechanical; I looked down.

A beetle like a bronze leaf

was inching across the cement...

or

there is no end to that which,

not understood, may yet be noted

and hoarded in the imagination. . .

These and later poems of dawning consciousness and ‘blood and family’ and were both preternaturally clear in their sharply focused attention on details of places and people and at the same time slightly blurred, their back stories withheld, their architectonics complicated. To read them is to be plunged without preamble or introduction into their immediate, urgent world. ‘I was going to say something/and stopped.’ (‘Ancestor’)

or

I was sent in to see her.

A fringe of jet drops

chattered at my ear

as I went in through the hangings.

I was swallowed in chambery dusk...

They’re also strangely self-sufficient – they confound the usual expectation of resolution and closure and are open-ended, the dynamic intensely personal. What stops them from sinking into unmediated privacy is the force of their realisation as verbal objects. The paradox of Kinsella’s work is that it often uses very personal material with the flinty objectivity of a Tribunal report. It is part of the process to which the poet subjects his material in order to extract the essentials. The challenge for readers as they follow the poet on his journey to the interior is to learn how to read a poet who resists the usual comforts. Eamon Grennan has said his poems must be experienced rather than understood, and Dennis O’Driscoll once likened reading him to adjusting to the dark in a cinema: ‘you do gradually become accustomed to the kind of atmosphere and the kind of light that you’re working in.’

Our sense of Kinsella, and Kinsella’s Dublin, is greatly amplified by a new book, Thomas Kinsella: A Dublin Documentary, published by O’Brien Press, which presents twenty key Kinsella poems alongside comments, family photographs, prints and other material. The book places Kinsella solidly in his Dublin context and charts the growth of his self-awareness as man and poet. Much of what would have been inferred about the life is now explicit. It fills in gaps, names names: the Kinsellas and the Casserlys and their lives in Inchicore and Kilmainham, a brief spell in Manchester and the family’s return to a Dublin ‘of displacement and unemployment, and short stays in strange houses’. It fleshes out the gallery of strong, definite characters that people the poems: the ‘Boss’ Casserly, Grandfather Kinsella the repairer of shoes and their formidable wives, both of whom ran small shops in their houses:

It was in a world dominated by these people that I remember many things of importance happening to me for the first time. And it is in their world that I came to terms with these things as best I could, and later set my attempts at understanding.

A great deal of Kinsella’s poetic energy still streams from these places and people and that growing self-awareness. Many familiar poems now appear accompanied by family photographs or laconic comments, such as the following after ‘Hen Woman’ : ‘A scene ridiculous in its content, but of early awareness of self and process: of details insisting on their survival, regardless of any immediate significance’. ‘All of these poems,’ he reminds us after ‘38 Phoenix Street’, ‘whatever their differences, have a feature in common: a tendency to look inward for material – into family or self.’

Kinsella’s work in the Land Commission and later the Department of Finance at a time of rapid economic expansion gave another dimension to his work but also further reinforced his steely methodology as a poet. His days began with a walk into Government Buildings and a view of the vista that would give his own Peppercanister Press its name when he began issuing his work in carefully worked sequences, applying the same thoroughgoing control to the process of publication as he applied to the material itself. The Department helped him, he says here, ‘towards viewing things directly. Staying with the relevant data, and transmitting them complete.’

The relevant data, for Kinsella, include the full span of human experience and the huge variety of response the human spirit and psyche has evolved to process it. This means that you can never separate the public from the private Kinsella, you can’t say here is the Dublin of personal memory and here is the public entity, or here is the public and here the private voice. The nature of his pursuit is to find a way of writing which incorporates all of these and moves, often disconcertingly, from one to the other, from Robert Emmet on the scaffold to a Malton print of Thomas St in 1792 and on to the murmur of personal recollection.

The bus tours may not be about to start, but Thomas Kinsella here gives us a valuable key to understanding some of the ‘established personal places’ that continue to absorb and radiate his imagination’s heat.

With acknowledgements to The Irish Times, where this piece first appeared

Thursday, March 08, 2007

Hugo Claus

Interesting piece by J.M Coetzee in the Guardian on the Flemish writer Hugo Claus. Claus is an extraordinarily prolific novelist and playwright as well as a poet who who has published over 1300 pages of poetry. The Guardian also reprints 'Ten ways of Looking at PB Shelley', one of the poems which Coetzee translated in Landscape with Rowers - An Anthology of Dutch Poetry which came out a couple of years ago. Some of Claus's work is also featured on Poetry International's site here.

A brief review of Greetings can be found at the complete-review.

Selective translations of poetry

Selected poems, 1953-1973. Portree : Aquila Poetry, 1986.

The sign of the hamster. Leuven : Leuvense Schrijversaktie (European Series 65), 1986.

Greetings - Selected poems. New York: Harcourt Brace, 2005.

Landscape with Rowers - Anthology of Dutch Poetry. Edited and translated by J.M. Coetzee. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Saturday, March 03, 2007

In the graveyard

I'm putting this up for a couple of weeks as people have been looking for it. It seems to be on the list for a poetry speaking competition. The book can be tricky to get outside Dublin (though you can try Gallery Press if you want to feel virtuous and buy a copy). Just don't forget, if you win the competition you'll have to send me a large amount of money.

from Nonetheless, Gallery Press, 2004.

In the graveyard

They lived and died in the same place.

The same names occurring, same big skies above.

This close, they must move still in their cottages

and walk their fields, or stand now watching

the mountains purpling in the last sun

and hear the sea turning onto the slope of the beach

its calm, insistent weight. The air’s crowded with them

as they move and watch and listen, no-one

having told them otherwise. And if

absentmindedly they drift back here

to this silent field, they’ll find

the gate locked before them and their names

unreadable on the stones. They’ll walk back towards the village

and climb into their beds, whatever was theirs still theirs.

from Nonetheless, Gallery Press, 2004.

Friday, February 23, 2007

The Overgrown Path

Song

Even asleep, you’re everywhere.

You fall through the house,

right down to the small room

where I sit staring at the screen.

Your head rests on a blinking cursor,

there’s a menu for your toes,

you’ve somehow

drifted into the CD drive

and come out as Janacek,

the overgrown path, the barn owl

lifting its wings. You lurk behind my eyes

and broadcast from my bones

but even miles away, you’re on my tongue,

you’re banging down the door.

Sometimes I wake in dread

that you might have lifted off

like some bright machine

or vanished music, the owl lurking

in the dangerous dark outside.

What if I couldn’t hear you?

As if there were anywhere now

out of reach, as if,

however late it was, or far

I wouldn’t hear you breathing

like a wing-beat in the blood,

a song passed from bone to bone. . .

Poetry Ireland Review 88

I have been working on the latest issue of Poetry Ireland Review, no 89, and realised I neglected to give the current issue a mention here, so here goes. Issue 88 has new poems by Kit Fryatt, Paul Batchelor, Liam Ó Muirthile, George Szirtes, Louis de Paor and many others. There’s a Dutch language feature with poems by Rutger Kopland, Dirk van Bastelaere, Hans Faverey and Cees Nooteboom. Eamon Grennan is interviewed by Catherine Phil McCarthy and reviews include David Wheatley on Roy Fisher; Peter Pegnall on Tony Harrison and Michael Foley; Maurice Harmon on Anthony Cronin; Richard Tillinghast on Greg Delanty; Chris Preddle on Paul Muldoon; Maria Johnston on Michael Longley and Peter Robinson on The Bloodaxe Book of Poetry Quotations.

The Orpheus File

Some links on Don Paterson's Orpheus (Faber, 2006)

'Translation shows us how poetry works - and reminds us why it matters' Don Paterson's New Stateman piece on translating the Sonnets to Orpheus

Interview with Don Paterson in The Guardian

Adam Philips on Don Paterson's Orpheus in The Guardian

Jeremy Noel-Tod's Telegraph review

Translations of The Sonnets to Orpheus by Howard A. Landman along with links to other translations.

This is from Stephen Cohn's Carcanet Press version

Don't depend on it, but here's the Wikipedia entry on Rilke. Some good links.

'Translation shows us how poetry works - and reminds us why it matters' Don Paterson's New Stateman piece on translating the Sonnets to Orpheus

Interview with Don Paterson in The Guardian

Adam Philips on Don Paterson's Orpheus in The Guardian

Jeremy Noel-Tod's Telegraph review

Translations of The Sonnets to Orpheus by Howard A. Landman along with links to other translations.

This is from Stephen Cohn's Carcanet Press version

Don't depend on it, but here's the Wikipedia entry on Rilke. Some good links.

Thursday, January 18, 2007

Pessoa: The Exhausting Electric Trolley Car

All night I have dreamt of tobacco,

of a world filled with smoke

and governed by tobacconists.

I work my way back to you

through generations of cigarettes

rollups tailormades filtered, unfiltered

fat and thin, menthol and acrid

some coloured and some with cards, pictures

a world of dead stars and football players

a world all lips and fingers

I light my way to a dark café

the smoke from my own cigarette ending

in the smoke that billows above your head

that is your life, inhaled then with a flourish

expelled, to entertain the air, to go nowhere.

Tobacco-haunted I wander

through rooms rank with the odour...

For some years now I have been trying on and off to write a poem for and about Álvaro de Campos, trying for lines that would get at the essence of this elusive personality and the body of work created out of it; lines that might also be spoken by a near relative of de Campos, that would be, in the ancient tradition of clumsy homage, approximations of the poet himself, mimetic alignments with his spirit. De Campos is a loose, expansive poet, described by himself as a Whitman with a Greek poet inside. He studied mechanical and then naval engineering in Glasgow, but gave it up. He was taught Latin by his uncle, a priest. He was never seen without a monocle. He wrote an energetic poetry about home, homelessness, placelessness, restlessness, selflessness, in the sense of having no definite self. ‘I’d like to have strong convictions and money’1 he says in ‘Opium Eater’, but ‘I’ve no definite character whatever’. He sees himself as ‘a continual dialogue’, a ‘solemn investigator of useless things’. He likes to strike poses of fin de siècle ennui:

I belong to a type of Portuguese

Who since discovering India

Has been unemployed. Death’s a certainty.

I’ve thought about this a great deal.

The condition described in de Campos’s poems is of a generous lyric intelligence energised by the lack of precisely those qualities we usually expect from a poet. He apprehends the world but he lets it wash over him without any attempt to wreak order on it. He is a havoc of negative capability. ‘Nothing holds me to anything./I want fifty things at once’ he half laments, half boasts in ‘Lisbon Revisited’, and he goes on to construct his aesthetic out of nothing, and out of undifferentiated and multidirectional longing. Not even dreams supply conviction : ‘Even my dreams felt false as I dreamed them’. His favourite action is inaction: what he does best is smoke cigarettes, and tobacco has a privileged place in his image stock. Nunca fiz mais do que fumar a vida (I have never done anything but smoke life away). The cigarette is oblivion and deliciously savoured wastefulness, ‘the freedom from all speculation’. Self-knowledge begins for de Campos in self-extinction:

I’m beginning to know myself. I don’t exist.

I’m the space between what I’d like to be and what others made of me.

Or half that space, because there’s life there too...

So that’s what I finally am...

Turn off the light, close the door, stop shuffling your slippers out there in the

hall.

Just let me be at ease and all by myself in my room.

It’s a cheap world.

Álvaro de Campos, the breezy, self-extinguishing Portuguese modernist walking his thin line somewhere between Whitman and Surrealism, has a particular fascination for me because, of course, he doesn’t exist. Or does he? Certainly not in the sense that we here do, with our blobs of fleshly apparatus. He is one of the heteronyms of the great Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa, along with Ricardo Reis and Alberto Caeiro. Pessoa’s creation of these entirely distinctive poets, each engaging with the other’s work so that collectively they amount in effect to a literary movement, is one of the great leaps of the modern poetic imagination, and it perfectly dramatises one of the central dilemmas of poetry from the latter decades of the nineteenth century through the fraught ground of modernism to our own day.

That dilemma might be summed up as an increasing uncertainty about an increasingly complex set of responses to the positioning of the ‘I’ in poetry: the dissolution of the Romantic sense of self into a room full of competing selves. Rimbaud’s ‘ ‘Je’ est un autre’ is the first step on the journey that leads to the linked but separate achievements of the four imaginary Portuguese poets, of which Pessoa himself must be counted one. To say that the ‘I’ is other is to recognise the necessary fictionality of the writing persona, to define the shift from an empirical to a poetic self that takes place as soon as anyone sits down to write a poem. The fact that a great deal of poetry acts as if that shift were not there shouldn’t persuade us that there is such a thing as an innocent primal empirical self moving seamlessly from the lived life to the written life. Yet much of the most exciting, the most genuinely engaging poetry of our century proceeds from a recognition and even embracing of the fluid, dissolving self. Part of what I want to argue in this essay is that in many respects and for a variety of reasons we are witnessing a return to a more limitingly personalised concept of what it is to be a poet and that many poets are no longer interested in taking the risk of forgetting who they are.

‘To pretend is to know oneself’ Pessoa said, and his whole life was spent in a trance of pretence. Self-extinction and self-creation were the two parallel drives which impelled him, as they did the heteronyms. For Pessoa, in fact self-extinction and self-creation were one and the same thing. He created his first heteronym at the age of six, the Chevalier de Pas, ‘from whom I wrote letters to myself’. The grammar of that phrase suggests the degree to which self division was instinctive to Pessoa. The fact that the only books published in his lifetime were of his English poems points up another kind of division — Pessoa was taken to Durban as a child and educated at an English-speaking school. Poetically he was a latecomer to his own language.

I want to go back to the day Pessoa called ‘the triumphant day of {his} life.’ It was the 8th of March, 1914 and after some attempts at creating a complicated bucolic poet he walked over to a high desk and wrote, standing up,

some thirty poems, one after another, in a kind of ecstasy, the nature of which I am unable to define. It was the triumphant day of my life, and never will I have another like it. I began with the title, The Keeper of Sheep. What followed was the appearance of someone in me whom I named, from then on, Alberto Caeiro. Forgive me the absurdity of the sentence: In me there appeared my master.2

Pessoa describes a process which is as remarkable for the order in which the events took place as for the events themselves. Once he had created Alberto Caeiro he immediately wrote the six poems of the sequence ‘Oblique Rain’ by Fernando Pessoa. ‘It was the return of Fernando Pessoa/ Alberto Caeiro to Fernando Pessoa himself. Or better, it was the reaction of Fernando Pessoa against his nonexistence as Alberto Caeiro.’ It took an act of creative self-obliteration to release the entity that was the poet Fernando Pessoa, to present him so completely with the possibility of his own extinction that he could either vanish from himself or struggle to leave his own imprint on the page. What Pessoa describes here is a reversal of the order we might expect: of the poet’s inventions taking flight from an established poetic presence. It is unusual to witness the invention preceding the self-creation; it is unusual to watch, as we watch Pessoa here, a poet go to the outer reach of the territories within which the self exists, and recognises its own existence, and then return intact, as, remarkably, his own disciple.

What are the implications of that reversal? What does it tell us about the way in which the poetic imagination functions? It should at least re-alert us to the way in which the writing of a poem can proceed from the same sort of creative fracture that opens up a work of fiction, and remind us that the same multi-levelled response caused in us by the interplay of narrator, characters and language is available to us when we encounter whatever self is projected in the lines of a poem. It should also, perhaps, make us wary of accepting at face value even — or particularly — the most seemingly transparent ‘I’. Not every poet possesses the set of emotional and psychological imperatives that drove Pessoa to his particular self subdivision. Nor does every poet seek to build an aesthetic from a primal awareness of the multiplicity of possible selves out of which, either individually or simultaneously, contrapuntally, a poem might be written. It might also be said, to shift the argument sideways a little, that Pessoa’s foregrounding of the whole question of self in poetry accords with a European or at any rate a non-anglophone fluidity of approach. If it is hard to imagine Pessoa in English, as I think it is — and discarding for a moment the fact that Pessoa actually began as a poet in English — part of that difficulty of imagination is that English as a language, and more precisely as a literary language, comes freighted with a level of concreteness, and specificity that impinges on the way in which the poet exists in the world.

Let me attempt to clarify this by recourse to those old allies of sloth, simplification and generalisation. Let us imagine, Pessoa-like, two prototypical poets, one anglophone and one a composite European. Frederick Steel and Jorge Bonacordia have met at an international poetry conference and, in an idle moment, have been scanning each other’s work. Frederick is bothered by what he sees as the unaccountable abstraction of Jorge’s poems. It never seems to be quite clear what is going on, or who is being addressed. The visible world seems to be very skeletally embodied in these lines. If there is an undifferentiated tree, or bird or rock that’s about as concrete as it gets. If something specific and recognisable does appear, a carob-tree, a salamander climbing up a wall, it seems to function in an altogether different manner and to engage the poet’s consciousness at a level as subliminal as it is unparaphrasable. Jorge for his part is bemused by the glutinous mass of material information which Frederick Steel’s poems expect him to digest. Several kinds of tree and species of insect are named and evoked in alarming detail. The poems seem to be structured around things that have happened to the poet and his immediate family or to relate feelings and thoughts by means of stories told to allow the poet to reveal himself to us. Jorge feels as if someone has grabbed the lapel of his jacket and is threatening to stay until he has dredged up every last detail of his biography, sprinkled with what he thinks these details mean in the scheme of things. They consider each other blankly from across the table. They plot escape.

This is a cartoon, though after I drew it I came upon an interview with the English poet Stephen Romer where he referred to what he called ‘the post-Mallarméan reflexiveness and theory’ which further differentiates (and alienates) contemporary French poetry from its English counterpart, and remembered a Cambridge Poetry Festival where a French poet declared that an English poet’s poem about a garden was not a poem at all ‘because it didn’t discuss itself enough’.3 I’m tempted back into my own cartoon every time I read a book of poems in English that depends on my receptiveness to the projection of the single persona of the poet’s self and the reliance on a treasure trove of largely unmediated personal information.

Or again when the poet and his/her audience are locked in a relationship that expects the poet to articulate on behalf of some larger societal set of aspirations, to be a messenger or vates. For it is in fact a short leap from the security of the individual self plunged in a self renewing circle of personal concern to the kind of self certainty that can allow a poet to assume a role of public iteration, no matter how complex the relationship between poet and audience. It does seem that anglophone poets are more likely to blur the distinction between the poetic and empirical self and be subject to a set of audience expectations that also depend on that blurring. Anyone who has opened a magazine and seen, for instance, an Irish poet castigated for failing to deal with ‘the situation’ or an English poet because he or she has, regrettably, not experienced an acceptable level of oppression, poverty, censorship and produced a body of work which satisfies the liberal need for moral applause as much as it asserts human decencies, knows the route where that kind of blurring all too often leads. For again, it isn’t a big step from the idea of a poet as a clearly identifiable and pinnable-down entity to a reflexive prescriptiveness of the audience or critic.

Again, this is why most of our discussion of poetry take place on a thematic plane, where it is the poet’s quantifiable ideas and feelings which matter rather than the manner of their expression. On the other hand, to encounter poetry from outside this tradition is to realise the many different modes in which the poetic consciousness can operate. Writing on René Char, Yves Bonnefoy, Henri Michaux and Philippe Jaccotet—translations of whom have recently become available in dual-language editions published by Bloodaxe — Malcolm Bowie commented that all four are ‘writers who uncouthly refuse to be interested in manners and customs, or in the invisible contractual arrangements by which social groups perpetuate themselves. Each one is a monad, and proud of it.’ (TLS, January 27, 1995, p 11). This is not to say that an interest in society’s ‘invisible contractual arrangements’ is an exclusive property of poetry in English, but it does point up an interesting difference in the relationship between poet and reader, and that between the poet and the poetic consciousness.

Nor am I implying that the notion of a depersonalised self in English is new. If I seem to be eliding the achievements of Eliot or Pound or Stevens or the floating indefiniteness of a contemporary figure like Ashbery, it is in part because they are exceptional figures, but also because the radical redefinitions of the self that are central to their poetry have taken rather different forms than those of Pessoa, or, again to take a random sampling, Bonnefoy or Char or Lorand Gaspar or Montale. But the anglophone poets came to the question from a different context and devised quite different escape routes from the tradition of the foregrounded self which they inherited. Eliot was, after all, the famous exponent of poetry as an escape from self, even if he did put the argument in terms which suggested that it was self replacement rather than escape that he had in mind, a replacement necessitated by a host of emotional and intellectual rejections and realignments. The surfaces of Eliot’s poetry fairly glisten with the authority of a style or the style of an authority quite as meticulously arrived at as Pessoa’s transformations. The same might as easily be said of Wallace Stevens or Ashbery. Yet the very distinctiveness of their styles, the unmistakable modulations of the voices that speak their poetry illustrates their remove from the slippery Pessoa. We cannot easily recognise Pessoa, though we might catch the tone of de Campos, or Caeiro or Reis.

Analysing his own condition, Pessoa goes back to Aristotle’s division of poetry into lyric, elegiac, epic and dramatic and argues that despite the usefulness of Aristotle’s scheme, literary genres are not so easily separated out.

On the first level of lyric poetry, the poet who is focused on his feeling, expresses that feeling. If however, he is someone of many different and shifting feelings, his expression will take in a multiplicity of characters unified only by temperament and style.4

Pessoa pursues the levels of lyric poetry up a ladder of increasing depersonalisation and multiplicity. The farther up the ladder the poet progresses the greater is the fracture between the empirical and poetic selves. On the next rung is the poet ‘of varied and fictive feelings, given more to the imaginative than to sentiment and living each mood intellectually rather emotionally.’ Pessoa is describing the progress of what we might call the sympathetic imagination: variety, fiction, intellect assuming primacy over direct lyric apprehension of emotion. The poet on this level expresses himself through multiple characters ‘not united by temperament and style’. Further up again the ladder of depersonalisation or of the imagination —for the two are in fact synonymous for Pessoa — is the poet of shifting moods, giving himself over to each mood so fully that the style varies. On the final rung you have the ultimately depersonalised poet, the poet like Pessoa himself who is ‘various poets, a dramatic poet writing lyric poetry’. Here, each mood becomes a distinctive character with a quite separate style and also — and this is a crucial element in the theory of depersonalisation — ‘with feelings that differ from, even contradict, the feelings of the poet in his living person’. Thus, Pessoa warns us explicitly against identifying any of his heteronyms with himself, and even makes it clear that they express sentiments he himself finds unacceptable. He also licences them to freely contradict themselves. So Pessoa constantly disappears from his own creations, and from himself. How much his work, and his whole personality, depended on this quality of disappearing, of melting into the world, is evidenced by another journal entry:

I have all the qualities for which the romantic poets are admired, even the fault of such qualities by which one really is a romantic poet. I find myself described (in part) in various novels as the protagonist of various plots, but the essential thing about my life, as about my soul, is never to be a protagonist.

I’ve no idea of myself, not even one that consists of a nonidea of myself. I am a nomadic wanderer through my consciousness.5

Each of the heteronyms embodies Pessoa’s depersonalisation and the poetry of each is both a celebration of the objective world and a personal vanishing act. The different oeuvres also manifest various forms of the sympathetic imagination: the imagination that goes out from the poet and centres itself in the world as it impinges on the poet’s senses. Caeiro, the father-figure, is a spiritual shepherd, a pastoral pagan who identifies completely with the seen world. His poetry is a way ‘of being alone’; he is without ‘ambitions or desires’. He has no sense of self out which ambitions and desires can grow. He believes in the world because he sees it and because he doesn’t think about it or make of it a mystic embodiment of some other reality. His whole philosophy is the absence of philosophy. ‘I have no philosophy: I have senses’, he tells us. The Keeper of Sheep does project a kind of anti-religion, a blasphemous subversion of Christianity: his Christ is radically ordinary, a refugee from his own fate who creates himself ‘eternally human and a child’ who teaches Caeiro how to look at things and let them be themselves. Caeiro allows himself to be a mystic ‘only of the body’; he doesn’t know what Nature is and if he occasionally yields to anthropomorphism, having his ‘flowers smile’ and ‘rivers sing’, it is because this is the only way to ‘make deluded men better sense/The truly real existence of flowers and rivers.’ Caeiro lives in a state of creative denial: the very first words he utters to us, the lines which open The Keeper of Sheep, are ‘I have never kept sheep’. His life is a self-conscious pastoral fiction constructed to deny the fictions of philosophies and systems: what he offers is a brusque materialism, most clearly argued in the poem he wrote some years after his death — a poem, that is, which postdates the lifespan accorded him by Pessoa— :

Sometimes I start looking at a poem.

I don’t start thinking, Does it have feeling?

I don’t fuss about calling it my sister.

But I get pleasure out of its being a stone,

Enjoying it because it feels nothing,

Enjoying it because it’s not at all related to me.

Later on he denies the accuracy of a phrase like ‘materialist poet’, and the concluding lines perfectly sum of the fate of the poet burdened and lightened by a sympathetic imagination:

I’m not even a poet: I see.

If what I write has any merit, it’s not in me;

The merit is there, in my verses.

All this is absolutely independent of my will.

The world happens to the poet, it rests on his senses alone and requires nothing of him but his apprehension of it. Caeiro comes out of nothing, according to his disciple Ricardo Reis, ‘more completely out of nothing than any other poet’. He comes without baggage, with his senses for tradition: a perfect tabula rasa , on which the world can inscribe itself. This notion is surely problematic for many of us. Is the poet an empty jug waiting for the world to tumble in and be embraced; waiting for the jug to empty and fill again, accommodating each burst from the tap with the same clear-eyed equable poise? Isn’t this too passive? Don’t we want our poet to engage with the world from the vantage point of some hard won singular vision, to filter it through to us in the light of that individual fire?